Rethinking how we design clinical studies

18 May 2021

Apple co-founder Steve Jobs said, “It’s really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”

But the truth is Apple actually does a huge amount of market research for their products. When first developing the iPhone, they needed to know what people wanted (e.g., battery life, screen size, cost) before investing huge amounts of money in development, mass production, advertising and sales.

And they got it right.

Flip phones and slide phones of the mid-2000s are thrown to the background.

Just like the iPhone, a clinical study is part of the development of an idea — it might be a new intervention such as a drug or technology, or a new way of organizing our health care system.

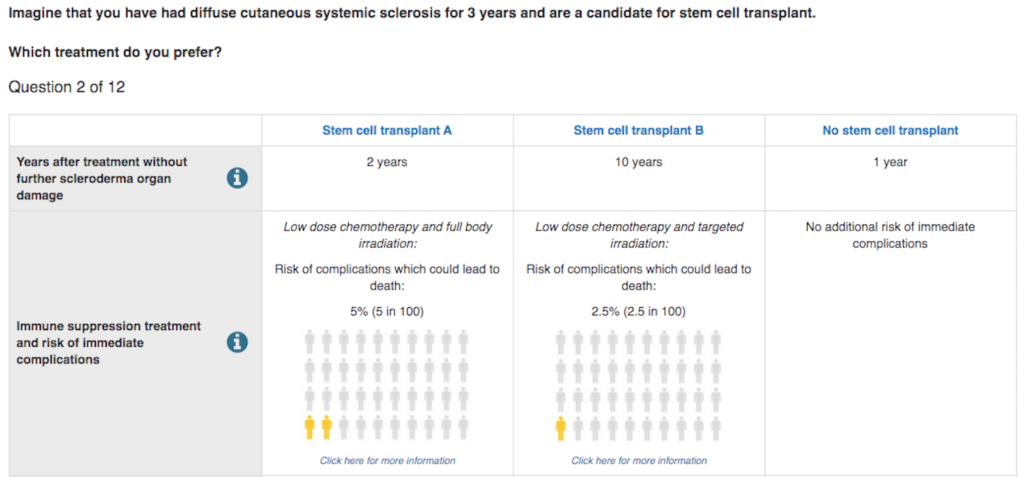

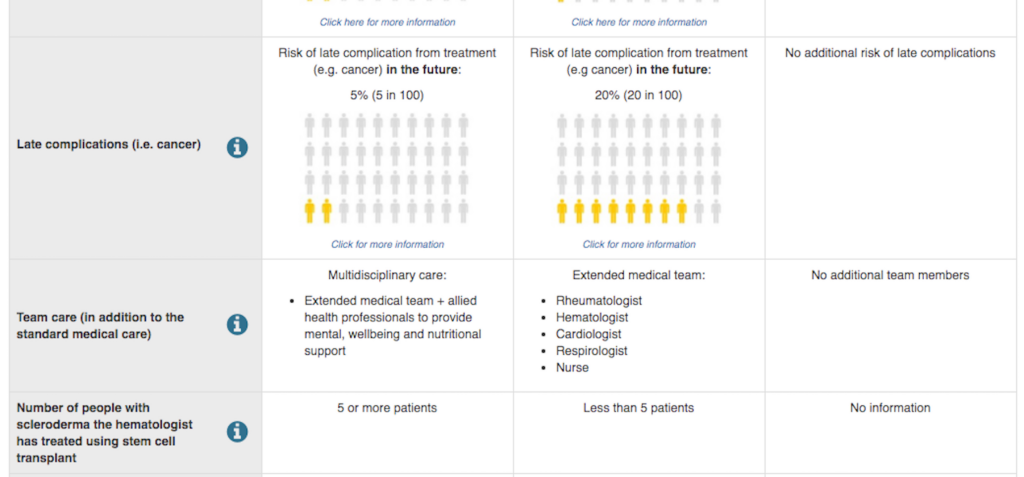

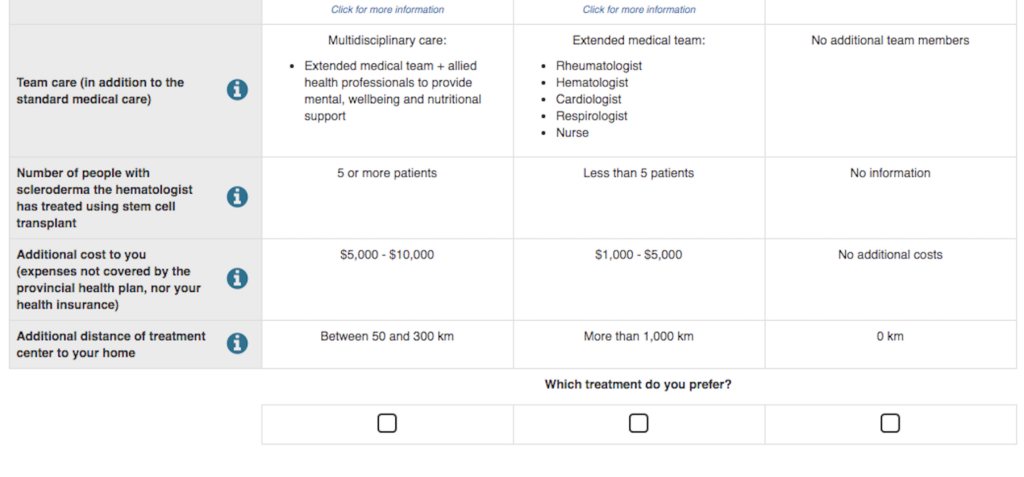

In our study, we took a look at a trial of patients with scleroderma evaluating the desirability of stem cell transplants. Stem cell transplants have been shown in previous studies to potentially extend life, but at the cost of considerable risks (e.g., surgical mortality, side-effects) and interruptions (e.g., travel to clinics) to the lives of patients through months of treatment. The main trial that set out to test stem cell transplants struggled to recruit enough patients and had to report the results based on smaller numbers of patients and change the outcome measure they were using. The new outcome measure grouped a broad range of potential outcomes together and so was difficult to interpret whether the potential benefits outweighed the harms.

What if they could predict these challenges before going ahead with the trial? It is just the same as Apple predicting whether the iPhone was going to be a success — they did this by asking potential customers what they wanted before they made the investment in development.

Most clinical researchers who come up with these ideas do ask… but the trouble is, they ask other clinicians, and not potential patients.

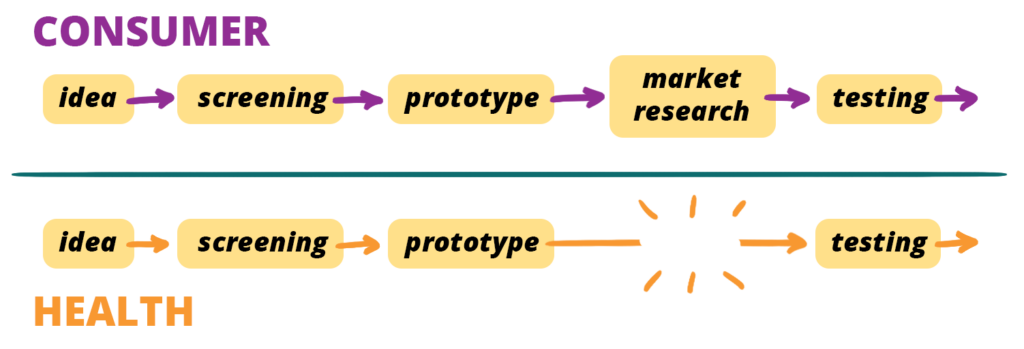

The two tracks align, except the “health” model has an obvious gap —

jumping from prototype to testing — skipping “market research”.

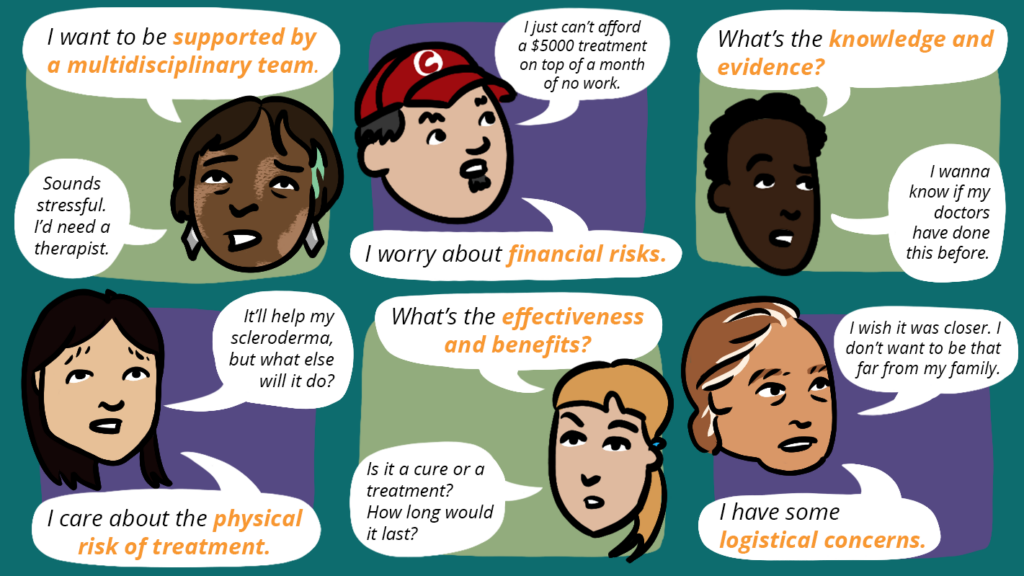

So, we asked patients. What did they want from their treatment?

As researchers, we usually expect patients to care most about risks and benefits. What surprised us was, that wasn’t their main concern. Instead, they cared just as much, or more, about having the care of a holistic, multidisciplinary care team. The quality of their care team, in fact, ranked higher in importance than whether the treatment had the potential to extend life, or carried risks of serious complications.

We would have missed this if we had just made assumptions about what patients want.

Download a screen-readable PDF version of this infographic.

But what should we be asking patients?

If we simply ask what people want, we will generate a list of desires with no sense of priority or importance. So it’s important to understand their trade-offs. Just like iPhone customers might want all the best features (unlimited battery life, the biggest screen etc), customers recognize that they can’t have all of these at the lowest, or indeed an affordable price, so they make trade-offs based on the features they most need and the budget they are working with. They might pay $700 for a phone with 10 hours of battery life, but not for 4 hours.

So, we constructed a survey that asked participants to choose between scenarios that had different ‘pros and cons’ for each aspect of treatment. Over 270 scleroderma patients answered our survey. From their data, we could make predictions about how willing patients might be to participate in different kinds of trials.

Our first results gave us confirmation that our method was working. We predicted that only one third of people with scleroderma would be willing to undergo the treatment that had been studied in the previous trial. This was the same recruitment rate that the trial had experienced: the trial could only recruit one third of the patients it needed to study its intended outcome.

But our next result was surprising. We predicted that if the trial had been designed to be more in line with what patients prioritize — with treatment closer to home, with financial support, and with a holistic multidisciplinary care team — that the willingness to undergo treatment could increase by 50%.

If the original trial had considered these factors, it could have met its recruitment targets. More importantly, if the trial was successful, the treatment provided would be appealing to far more patients in the real world. This means more patients getting the care they want.

When researchers assume that we know what patients want, our research suffers. When patients are involved — when we consider their priorities, their trade-offs, and furthermore involve them as partners through all stages of research — we’re improving our research, and its impact.

Find details about this study in our publication in Trials.

The Methods Clusters project studied the way that patient-oriented research is done, and how it could be better. In a series of blog posts, team members wrote about their work, what they learned and the best ways to engage patients in health research design. The BC SUPPORT Unit provided funding for the project.

This blog post was written by Nick Bansback and Mark Harrison.