Making a real difference: People who are incarcerated help peers get immunized for COVID-19

10 November 2022

“The beginning of the pandemic was really challenging for everyone, including people in corrections,” says Pam Young, manager with Unlocking the Gates Services Society. “Visitors were not allowed, and a 14-day mandatory isolation period for new intakes meant people had little time out of their cell. So, people were often forced to choose between making a phone call or having a shower.”

In early 2021, COVID-19 infection rates in BC’s prisons were unknown. However, measures to prevent transmission were having a negative effect on people’s wellbeing and access to justice. In addition to increased isolation, many vital mental health and wellness programs were limited or closed.

Sofia Bartlett, a senior scientist at the BC Centre for Disease Control, supported a survey to find out how many people were exposed to COVID-19 in provincial prisons. The survey was funded by Michael Smith Health Research BC to support rapid research related to the pandemic, as well as funding from the BC SUPPORT Unit (part of Health Research BC) for partner engagement.

Sofia had previously met Pam through another project, so she invited Pam to advise the study team. With Pam’s lived experience of incarceration, she provided guidance on how to design the survey. They found that COVID-19 infection rates were five times higher in BC’s prisons than in the general population at that time. They also learned that only 60 percent of people in custody wanted to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

Vaccines were one of the most effective ways to reduce the transmission of COVID-19 infection from earlier variants, especially in closed settings like correctional centres. Vaccination continues to be the most effective way to prevent severe illness and hospitalization. With these low predictions for vaccine uptake and the higher incidence of COVID-19 infection, there was concern about how these factors would affect the prison population. That’s why Pam and Sofia teamed up as co-investigators to help understand the barriers and enablers to vaccine uptake among prison populations in BC.

“Not accepting vaccines have real consequences for people in jails,” says Pam. “In addition to risking infection, people about to be released won’t be accepted into some housing if they aren’t immunized for COVID-19.”

In 2021, they launched a study to address COVID-19 vaccine concerns among people who are incarcerated provincially in BC. The study was co-funded by Genome BC, Michael Smith Health Research BC, and the BCCDC Foundation for Public Health.

They asked about people’s concerns around vaccines, what education they had received on vaccines while in custody, as well as the attitudes towards vaccines among people in provincial prisons. They learned that fear, mistrust and a lack of information were barriers to vaccine uptake in this setting.

“Getting immunized can be difficult for people who are incarcerated, who may fear needles or distrust health care,” says Sofia. “Without access to evidence-based information, misinformation was common. Our goal was to understand people’s concerns and ensure that people who are incarcerated are making informed decisions about whether or not to be vaccinated against COVID-19.”

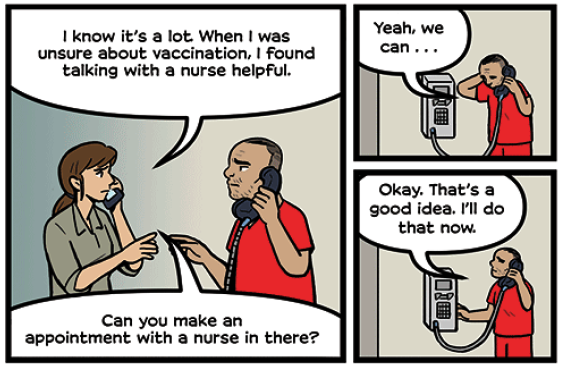

Sofia and Pam held focus groups with people who are incarcerated. They worked together to co-create educational materials that answered questions and concerns about vaccines for people who are incarcerated in a way that was engaging and understandable. The result was an evidence-based, peer-reviewed activity book: comic strips, crosswords, word search riddles and more.

Focus group participants rated the activity book as trustworthy and engaging. Now Pam and Sofia are poised for widespread distribution of materials among BC correctional facilities. They plan to measure vaccine uptake before and after the materials are broadly distributed.

By engaging people who are incarcerated and who have experience in corrections, the project was better able to address this population’s unique needs and perspectives. But developing targeted materials is only one benefit of the project.

“Research led by and with people with lived experience has benefits beyond answering our questions,” says Sofia. “This work allows people whose voices are rarely heard to feel respected and contribute to something meaningful.”