The Methods Clusters: Lessons in methods research

15 September 2022

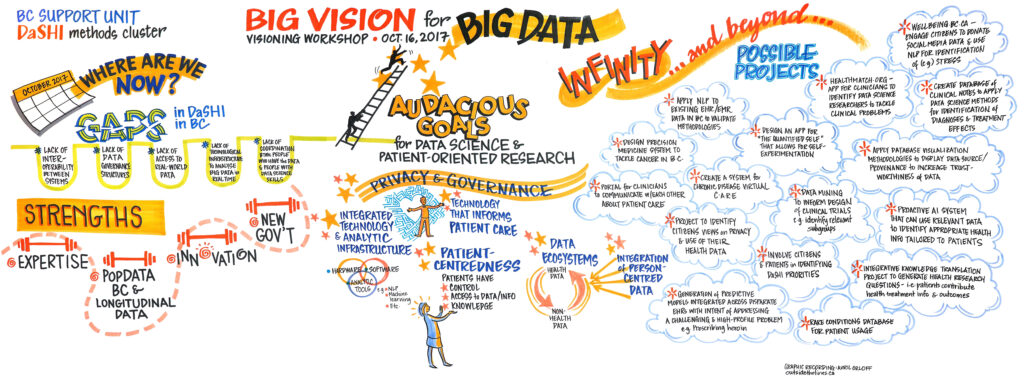

Image: “We know patient-oriented research is important. But how do we do it? And how can we do it better?”

What have we learned about how to do patient-oriented research?

The overarching goal of the BC SUPPORT Unit’s Methods Clusters was to strengthen patient-oriented research methods, with the aim of promoting research quality and delivering impact. This led us to establish six clusters, each focused on a different aspect of health research, and all tasked with investigating, innovating, or gathering evidence for the approaches we use for patient-oriented research.

Our work started in 2017, when the Methods Clusters were launched as a unique initiative of the BC SUPPORT Unit. A total of 42 methods-focused research projects were funded, spanning the six clusters, and all are now completed.

As we draw our Methods Clusters initiative to a close, we’d like to highlight some ways of doing this work — our methods — that helped shape some successes; and, to think critically about the roads left to travel. A major financial investment and five years of work has taken us a long way, but we also recognize that there remains work to be done.

Building the Methods Clusters

Where we started

In the spirit of patient-oriented research, all clusters embarked on their work through fulsome community consultation and dialogue sessions, to allow the research topics and priorities to emerge from stakeholder communities rather than research leaders alone.

Many of the research teams we supported were new to doing patient-oriented research. Much of the early and ongoing work of the Methods Clusters was, therefore, thinking about how to support these research teams doing things in a new way.

For example, one cluster (health economics & simulation modelling) took on this challenge by holding a series of community-building events that explored introductory patient-oriented research topics, works-in-progress, and other critical considerations, to support learning needs and promote knowledge sharing opportunities as a nascent knowledge community.

By bringing together new methods, ways of inquiry, and training of multidisciplinary teams, we were able to capitalize on broader strengths across the health research landscape and increase patient engagement in research along the way.

Learning and sharing

It is essential to recognize that patient-oriented research has a short history whereas other research areas — most notably, Indigenous research, community-based and other participatory research methodologies — have been engaging with people and communities for decades, if not longer. Celebrating the network of learnings from these knowledge communities, and providing mutual supportive pathways to share resources, was and is still key to ensuring that the wider research community is pulling together, not pushing apart.

For example, in Indigenous health perspectives, the singular focus on the ‘patient’ in patient-oriented research is antithetical to the embeddedness of individuals in family, community, and Nation contexts. Patient-oriented research and Indigenous research are clearly distinct, and those differences offer learning and growth opportunities, as well as terrain that require some negotiation, nuanced attention, and deeper work to find the right path.

One patient-centred measurement cluster project, which sought to develop culturally relevant patient-reported outcome and experience measures for Indigenous peoples and communities, describes ethical space as a territory that needed to be negotiated and established by Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers working together by acknowledging differences in culture and worldviews in a shared and respectful space.

Engaging patients

When doing patient engagement in research, some basics are important:

Respect the expertise of patient partners; use plain language; and ensure the time patient partners spend working on the project feels meaningful.

Methods Cluster teams found innovative ways to engage patients, often tailoring engagement to unique project contexts.

One project that worked with very frail, older adults, applied a ‘carousel’ approach wherein patient partners could ‘hop on’ and ‘hop off’ their engagement in the research project when health, energy, and commitments shifted throughout the process. To widen access and inclusion in patient-oriented research, it is critical that we find ‘solutions’ like this—that we consider and address what aspects of patient-oriented research may be set up and altered in ways that pose less burden on those who are the sickest, most chronically ill, and have the least resources to participate. This project innovated one possible approach. Could there be others?

Another innovative method of engagement was the piloting of an Elders-in-training program for a project on culturally relevant PROMs and PREMs for Indigenous peoples and communities. This team developed a training program where Elders mentored Elders-in-training to support ongoing cycles of knowledge-keeping, sharing, and exchange. This program was a small, but important way to address issues of Elders ‘burning out’ when asked by team after team to participate in health research; and, to address the importance of respecting Elders’ time and wisdom more generally.

It is exciting to see the relational ethics at play in the diverse methods our teams innovated and employed, which carefully ensure that the relationships established in research live beyond the immediate present, seeding positive impacts in the future.

Do we always need to engage patient partners in methods research?

We’ve learned from the Methods Cluster projects that we can engage patients to do methods research, and this engagement often benefits the patients and the project. But: does it always? Should we always engage patients in methods research?

As one Methods Cluster researcher noted:

“If we are inviting and engaging citizen patient partners, that creates an obligation for us to adjust. It’s not that we just say, ‘come into our world and observe.’ That’s so disrespectful. […] The invitation then comes with a sense of responsibility and accountability for us to make sure that there’s meaningful engagement of the people we’re bringing in.”

A research team is comprised of members typically serving different and delineated roles. In highly technical projects, like some of our statistics-based real-world clinical trials projects, there wasn’t a clear role for patient partners. To actively help with the project, highly technical knowledge was required — and at that point, what is really differentiating their ideas from that of a statistician or mathematician?

Perhaps “we” (the health research community involved in this work) need to more clearly define what ‘value’ patients bring to different types of projects, and how to set up patient partners to best ‘deliver’ that ‘value,’ as we do for all other roles on a team. Showing respect to a team member can mean giving them a clear role, because nobody wants to join a team and have nothing to contribute or feel disempowered by the context.

The BC SUPPORT Unit is well-positioned to help develop resources that consider, and present some perspectives on, these questions — and these resources are already available to some extent; however, research teams often need tailored, hands-on guidance to navigate their own contexts. This isn’t always a readily available nor a sustainable resource.

Continued Questions

Through rising tides of social unrest, societal injustice, and very unequal pandemic realities; our Methods Clusters teams all navigated pressing questions:

- How do we care for each other in this time?

- How are we, and our systems, set up to support good research, done in a good way, for good reasons, and for good impact?

- What changes can we and must we make to do research better?

We heard across our funded teams about how they addressed these ideas: increased measures of ensuring safety; learning more about and practicing humility; expanding our capacity to listen; finding new ways to meet people where they’re at; and growing not only awareness, but skills in navigating the question of “who is not in the room?”

But we are left with still more challenges relating to such topics as diversity and virtue signalling.

Diversity in patient-oriented research

Never has there been a more pressing urge to tackle inequities in whose lives are fraught, whose lives “matter,” and whose lives are privileged. Doors are opening to hard conversations around how to transform our health system in the wake of In Plain Sight, a global pandemic, and unprecedented deaths in the opioid epidemic; but, simply knowing that the work is important does not provide a road map (or a methods section 😉) on how to do the work.

In the patient-oriented research world, we’ve discussed at length how tokenism is a sign of addressing diversity badly. However, antidotes aren’t widely available to researchers. What, then, does it take to shift practice, build methods, and repair systems that are anti-racist, decolonizing, and restorative?

The patient engagement Methods Cluster identified early on that diversity was lacking in patient-oriented research and went on to address this in a number of ways and now offers exemplars of fostering diversity and equity at the methods level.

That said, we are still left with more questions. For example:

- How is inclusion/exclusion maintained or disrupted?

- How do we acknowledge, mitigate, transform structures of power? How do we navigate different privileges in the room?

- What tools are available to redistribute and share power?

- How does patient-oriented research allow individuals to show up but not communities?

Patient-oriented research & virtue-signalling

In her excellent and challenging keynote at the BC SUPPORT Unit’s 2019 conference, Jennifer Johannesen challenged patient-oriented researchers to consider what larger political agenda patient-oriented research might fit into. Are we inviting patient partners into heath research because it appears the right thing to do? Or are we truly committed to ensuring that pathways are put in place to make the changes that matter to our patient partners?

In reflecting on the collective work of the BC SUPPORT Unit’s Methods Clusters, have we served to sharpen the patient-oriented research tools in efforts to better serve the health research world? Or, have we supported some movement towards a more emancipatory, compassionate and humane health research system? It is probably too early to tell.

Amber Hui, Stirling Bryan & Danielle Lavallee

On behalf of the BC SUPPORT Unit’s Methods Clusters leads:

- Erin Michalak

- Hubert Wong

- Linda Li

- Bev Holmes

- Nick Bansback

- David Whitehurst

- Lena Cuthbertson

- Rick Sawatzky

- Kim McGrail

The Methods Clusters project studied the way that patient-oriented research is done, and how it could be better. In a series of blog posts, team members wrote about their work, what they learned and the best ways to engage patients in health research design. The BC SUPPORT Unit provided funding for the project.

This blog post was written by Amber Hui, Dr. Stirling Bryan and Dr. Danielle Lavallee.