A 20-year journey of health research in BC: An arts-based approach

14 July 2021

Photo credit: Prince George Citizen

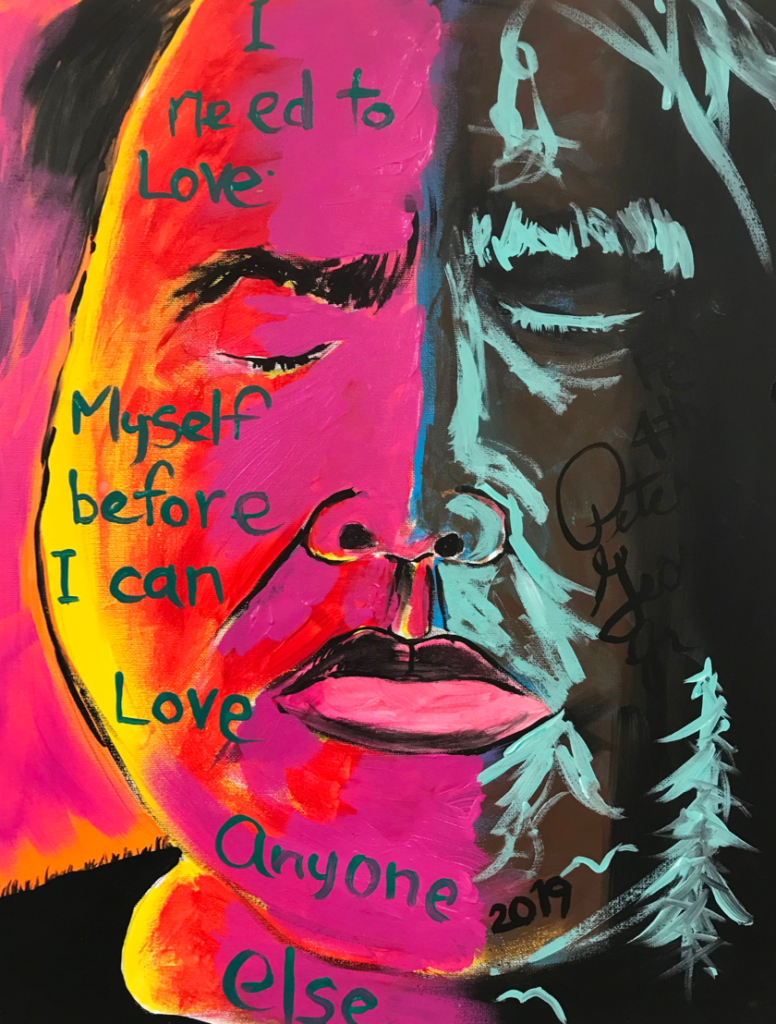

Dr. Sarah de Leeuw: An arts-based approach to health science

“There was another Sarah down the hall. I thought they had the wrong number.” Sarah de Leeuw was completing her PhD in Ontario and on her way to a Fulbright scholarship-funded fellowship at the University of Arizona when the University of Northern British Columbia’s (UNBC) Northern Medical Program, a distributed site of UBC’s Faculty of Medicine came calling. There was an opening to bring on a full-time professor, and they wondered if she would be interested in returning to BC to bring her art-based approach to medical education and research.

Having completed a Master’s thesis focused on BC’s notorious Highway 16, and a PhD examining children’s resistance through art in residential schools, the unusual opportunity was appealing. Raised in Haida Gwaii and Terrace, BC, Sarah was very driven to tackle, document and dismantle colonial structures that contribute to vast health inequities lived by Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in northern BC.

“It made good sense to me to twin arts-informed activities with questions about inequities that I witnessed,” Sarah explains about her drive to fuel research that would improve the well-being of people in rural and remote areas of BC. This long-held understanding was solidified at a young age, when she watched Bill Reid launch the famous LooTas canoe for Expo 86. “I have a very clear recollection of standing on the beach in Haida Gwaii, listening to people speak about LooTas being a statement of Haida strength and resiliency. That always stuck with me. Art has the strength to inform well-being and, ultimately, our health.”

“It made good sense to me to twin arts-informed activities with questions about inequities that I witnessed.”

Supported by UNBC, in 2008, Sarah set out a plan to creatively analyze traditional research questions to improve the health care system, then use culturally safe venues to share the findings about health and wellness. After learning that funding opportunities for arts-focused health research weren’t supported by social sciences funding agencies at the time, she began looking into alternate funding opportunities, which led her to apply for an MSFHR award. In 2012, she became the first MSFHR Scholar ever to be based in northern BC. Her award also marked the first time that MSFHR partnered with the National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health, ultimately leading to the creation of The Health Arts Research Centre at UNBC, which Sarah still leads today.

Sarah admits she was both relieved and surprised that MSFHR took a chance on her unconventional approach to health research. “It wasn’t a natural fit in 2010 when I started looking at health research funding. Much of health research is extraordinarily focused on quantitative efforts. In the last 10 years, this has changed, but back then it was definitely new. I’m glad. You can’t work with human beings without working with the whole.”

Sarah’s MSFHR Scholar award further increased the visibility and credibility of humanities-focused health research. In 2017, she was appointed as a member of the Royal Society of Canada’s College of New Scholars, Artists and Scientists, which recognizes multidisciplinary intellectual leadership. This also led to an appointment as the Canada Research Chair in Humanities and Health Inequities with the Canada Research Chairs Program in 2018, where she is one of over 2,000 world-class researchers across the country who reinforce academic research and training excellence in Canadian post-secondary institutions.

“We are supporting leaders in the north, from the north, to think creatively. It’s amazing that we are building these trainees into the health system, in great part because the Michael Smith Foundation funded our Health Arts Research Centre.”

Partially funded by MSFHR’s match funding, Sarah also received one of the first joint federal research partnership grants of its kind to be held at UNBC, and one of only nine such grants held across Canada. She currently leads a team of northern BC community advisors, health researchers and medical/health science students to develop and deploy multidisciplinary creative methods and methodologies to harness, document, translate and disseminate existing northern strengths — especially First Nations’ — as a population health and wellness initiative.

Sarah’s unconventional work to amplify arts-based health research, and train culturally safe health researchers in the north, has paid off. She recently mentored the work of UNBC-based researchers MSFHR 2019 Trainee awardee Dr. May Farrales and MSFHR 2020 Trainee awardee Dr. Vanessa Sloan Morgan. “We are supporting leaders in the north, from the north, to think creatively. It’s amazing that we are building these trainees into the health system, in great part because the Michael Smith Foundation funded our Health Arts Research Centre.”

She remains committed to dismantling colonial health care structures that do not work for northern populations. “When we can authentically realize how much we don’t know, we come closer to empathetic, sympathetic, culturally caring health care. This in turn helps to change hearts, emotions, attitudes, and understandings about the dynamics of our society that have led to colonial racism, genderism, ageism and placism, and move us towards a culturally human health environment.”

“Being a Michael Smith Scholar ensures that time and space have opened up for me so that I can concentrate on the most important aspects of my research, which are these pressing health inequalities in Northern and Indigenous communities,” says Dr. Sarah de Leeuw. Video credit: MSFHR, January 2015

Learn more:

MSFHR 2012 Scholar Award: Health, Creative Arts, and Northern Communities

MSFHR Announces First Partnered Scholar Awards (MSFHR, November 2012)