A 20-year journey of health research in BC: A rapid response to SARS

22 April 2021

Photo credit: BC Cancer and Michael Smith Laboratories

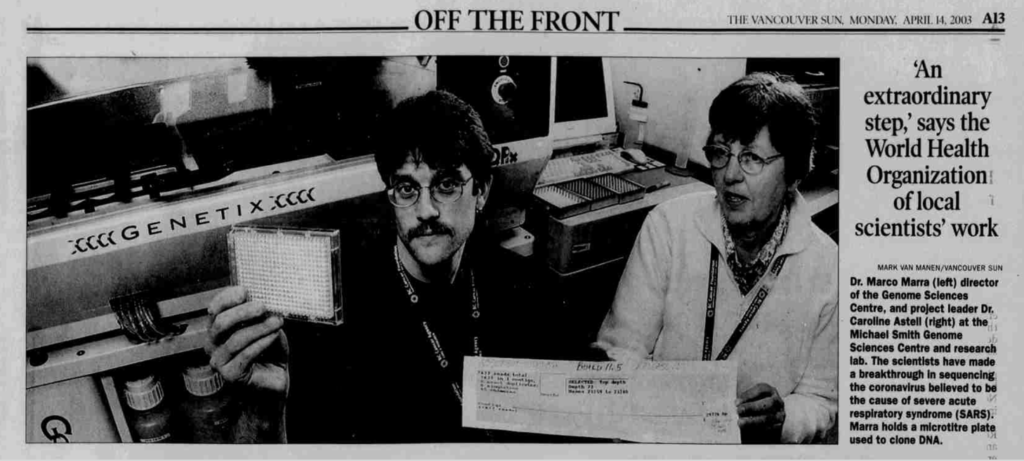

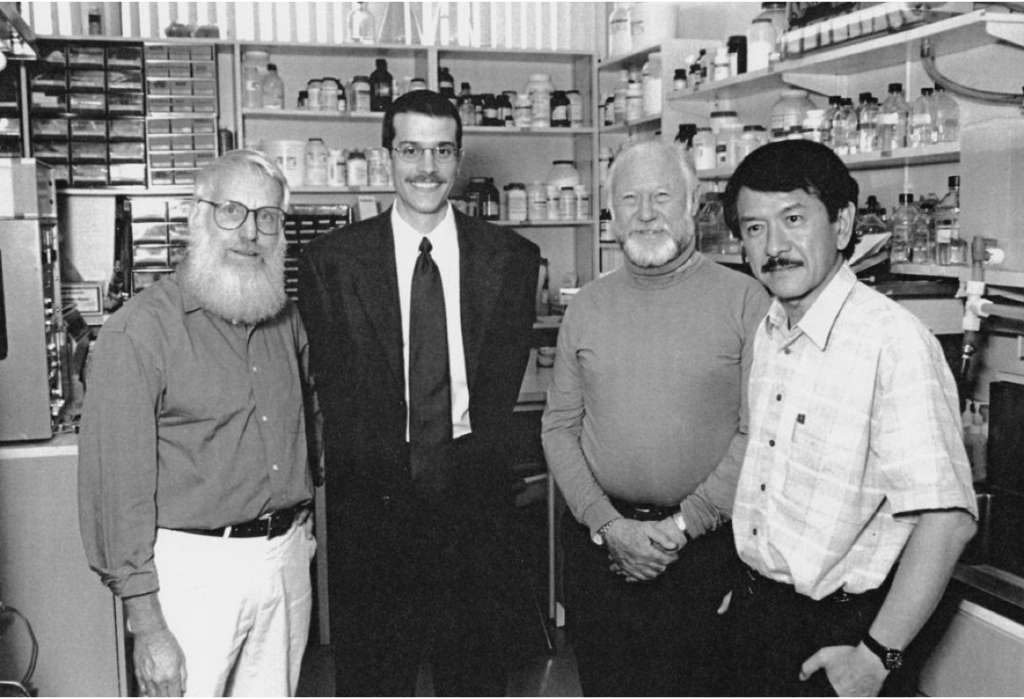

Drs. Marco Marra and B. Brett Finlay: A rapid response to SARS

“I probably should have been paying attention, but I was troubled and my mind was wandering. And I turned to Caroline and said: ‘We should sequence it, and then we would know.’ We talked it over, and then she called Bob [Brunham].”

It was early 2003 and MSFHR scholar Dr. Marco Marra recalls feeling very motivated to do something about this new thing called “SARS” that was making headlines. The deadly disease known as “severe acute respiratory syndrome,” or SARS, had already killed many people in Asia, and with the first Canadian case identified in Toronto, the community was feeling particularly tense and nervous.

Marco looks back on that moment and recognizes that virologist Dr. Caroline Astell’s call to Dr. Robert (Bob) Brunham at the BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) to ask for a piece of the SARS viral material was likely a bit out of the blue. But in the health research community, many people are more than happy to try to make a good thing happen.

That out-of-the-blue call led to a connection to Dr. Frank Plummer at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg, and Frank kindly sent a small drop of the viral material to the BCCDC in Vancouver, where it made its way to Canada’s Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre (GSC) at BC Cancer. Six days and six sleepless nights later, BC Cancer announced that GSC scientists had decoded the viral genome. This breakthrough confirmed the type of virus that caused SARS and provided the basic information needed to design methods to detect the virus and begin research to understand how best to combat SARS. This moment in early 2003 was a milestone event in health research history. A process that previously took years had taken place in just six days and put Canada and the GSC in the spotlight as the first lab in the world to sequence the SARS genome.

While the GSC was working on this sequencing, Dr. B. Brett Finlay received a call from Dr. David Patrick from the BCCDC. “What kind of science can we use to fight SARS?” he asked. “Can we make a vaccine or can we make a drug?” Brett remembers the anticipation in the research community and dropping everything to pitch the BC government on how his team planned to use the sequenced viral genome to create a vaccine.

Brett credits the partnerships and relationships in the BC health research system, and funding from MSFHR, for supporting the rapid response research for SARS, along with the then-unconventional approach of developing the solution in parallel, instead of waiting for each step to finish.

In fact, the lessons learned in 2003 informed global virology and pandemic response, allowing for continued rapid response, genome sequencing and health research improvement against viruses.

“It used to take 15 to 20 years to develop a vaccine,” Brett says. “But BC figured out how to move us all forward in the right direction, at the right time.”

With a concept in place, a few short months after the Genome Sciences Centre decoded the SARS genome, Brett’s SARS Accelerated Vaccine Initiative (SAVI) team, co-led by BCCDC’s Bob Brunham, put a plan in motion and rapidly developed three prototype vaccine candidates.

The SAVI team was fielding daily calls from around the world about their progress, so a weekly call was set up to share updates. To effectively counter SARS, the Canadian health research community knew they needed to work with researchers from around the world, and BC’s open information-sharing about the research process and findings was greatly appreciated. In fact, the lessons learned in 2003 informed global virology and pandemic response, allowing for continued rapid response, genome sequencing and health research improvement against viruses.

Both Marco and Brett credit MSFHR for the parallel funding streams that supported the researchers who sequenced the SARS genome and allowed SAVI to quickly develop the SARS vaccines.

“MSFHR has a wonderful way of finding star people, funding them, and letting them do the science they’re good at.”

“Many researchers have benefitted and have brought in great people. It’s given the province an identity,” Brett says.

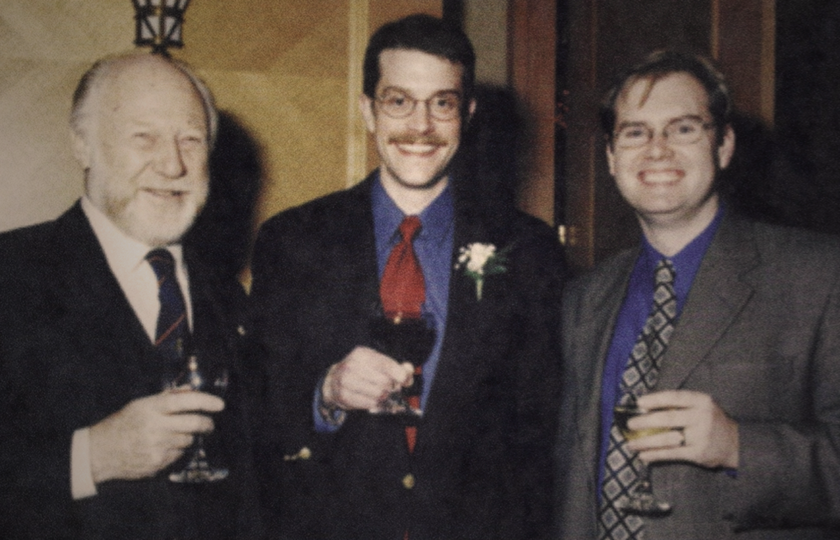

In looking back at this pivotal research moment in 2003, Marco reflects on the legacy of Dr. Michael Smith, the scientist with whom he and Brett both worked at different times before his untimely passing in 2000. “Science is practiced by people as they seek to unravel mysteries, and the successes and quality of science-based organizations are reflected in the people they support. I know that Dr. Michael Smith understood that, and MSFHR’s beneficiaries and their many accomplishments are a great credit to the organization.”

In 2001, Dr. Marco Marra was one of the first recipients of an MSFHR Scholar Award in recognition of his work in establishing Canada’s Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre. Team members who were part of the success in sequencing the SARS genome also went on to receive MSFHR awards, including Dr. Jaswinder Khattra, whom Dr. Marra credits for developing the material required to sequence the SARS viral genome.

Co-led by Dr. B. Brett Finlay, SAVI was funded with a $2.6 million provincial government grant through MSFHR, which provided the team with administrative, communications, and financial systems support.

Both Dr. Marco Marra and Dr. B. Brett Finlay were inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame, joining over 140 Canadian citizens whose outstanding leadership and contributions to medicine and the health sciences in Canada and abroad have led to extraordinary improvements in human health.

Learn more:

Dr. Marco Marra: At The International Forefront Of Pursuing A Genomics Answer To Cancer (MSFHR, Nov 2019)