Supporting health researchers during a pandemic: A research funder’s response to COVID-19

14 December 2020

Forward Thinking is MSFHR’s blog focusing on what it takes to be a responsive and responsible research funder. In this article, MSFHR Senior Specialist, Strategy, Maija Tiesmaki, reflects on how the COVID-19 pandemic affected BC’s health research community, the Foundation’s response, and how we’re continuing to support BC health researchers.

A pandemic and a pivot

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit British Columbia at the beginning of 2020, its effect on BC’s health research system and workforce was undeniable. The pandemic has been a watershed moment for science, upending universities, altering scholarly communication, and raising questions about the long-term impacts on research funding and priorities.[1] It has also highlighted the critical role of health research in generating the scientific evidence, tools, and discoveries needed to effectively respond to a public health emergency and save lives.

At MSFHR, we know that BC’s health researchers are committed to using their knowledge and skills to safeguard our health and the healthcare system we rely on. We acted quickly to support BC’s research response to the COVID-19 pandemic including funding urgent COVID-19 response research. We also saw a pressing need to understand more about how BC health researchers were being affected and what we could do to support them as the province’s health research funding agency.

From July to September 2020, we gathered comprehensive information about how the pandemic was impacting BC’s health research community. We:

- Consulted more than 20 senior health research leaders from around the province

- Reviewed emerging national and international literature involving more than 80 papers, studies and reports, about how COVID-19 was affecting research, funding and higher education, and

- Conducted a survey of ~300 BC researchers about the impact of COVID-19 on their health research, careers, and future plans.

Recognizing that the pandemic has affected everyone in some way, the core focus of our data analysis was understanding which BC health researchers were experiencing the greatest hardship and were most in need of support. This article shares key findings from this process, and actions we’ve taken to date to help BC health researchers amid the pandemic.

What we learned

How did the pandemic impact health research activities in BC?

Our findings confirmed that the COVID-19 pandemic had widespread impacts on BC’s health research capacity and workforce: 80% of survey respondents said the pandemic had a negative impact on their ability to conduct research, 48% said their research had been delayed or put on hold, and 60% said their workload had increased significantly. We learned about particular challenges by research area (pillar), linked to research curtailment and public health measures, for example:

- Biomedical researchers reported the greatest negative impact on their ability to do their research (90%) due to research curtailment and lab closures

- Clinical researchers described increased clinical workloads and issues progressing clinical research, with 83% facing challenges recruiting research participants

- Community-based researchers noted barriers to working with community partners and adapting to virtual research approaches. This particularly affected population health researchers (73%) and those based outside of the Lower Mainland (69%)

- Health services and population health researchers were most likely to report disruptions to knowledge translation (KT) activities, including a reduced ability to engage with groups outside of academia

Which researchers have been most affected by the pandemic?

Two groups of researchers in BC stood out in our analysis as being disproportionately impacted by the pandemic: postdoctoral fellows and early career researchers, and researchers with caregiving responsibilities, especially women.

“Early career researchers and particularly young women with families will face even greater equity issues. Women are more likely to take on household and childcare responsibilities at the expense of career progress.” – Mid-career researcher

Postdoctoral fellows and early career researchers

Before the pandemic, we knew postdoctoral fellows and early career researchers were facing a highly competitive funding environment and precarious academic employment, and it’s clear that COVID-19 has heightened uncertainty for these researchers at a critical point in their career development.[2],[3]

“I think post-docs are in a particularly precarious position. This is a time where we are meant to be ‘most productive’ and ‘prove ourselves’ and yet often we are unable to do our work (i.e., the universities limited access to labs for safety reasons).” – Postdoctoral fellow

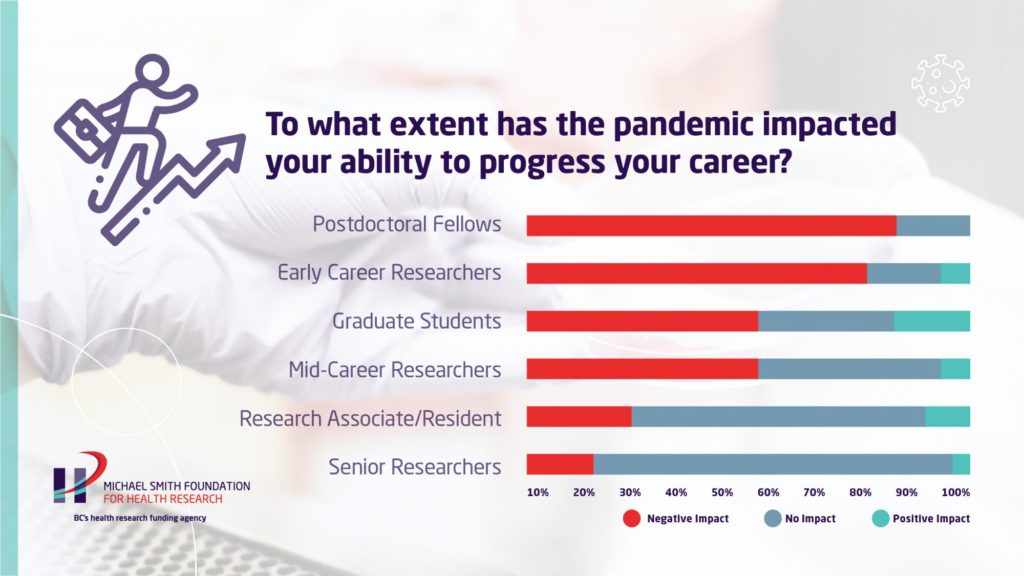

Nearly 90% of postdocs and over 80% of early career researchers who responded to our survey said the pandemic had a negative impact on their ability to progress their careers, and half of postdocs said it had significantly affected their research training.

We heard about delayed or halted research, lost opportunities for mentoring, networking, and collaboration, and concerns about employment and future career prospects. Several respondents spoke about the challenges for early career researchers, particularly pre-tenure faculty, to establish and grow their research programs and teams in the context of the pandemic.

“New faculty members, particularly underrepresented academic minorities, aren’t feeling very fit at the moment. We don’t have papers sitting on our desks waiting to be written. Our students are at the beginning of their training, and we don’t have core data and expertise to build from or use as preliminary data for our grants, and this disruption means it won’t be forthcoming any time soon.” – Early career researcher

Researchers with caregiving responsibilities

The pandemic is exacerbating existing inequities in research and academia [4], and there is evidence that women and parents with young children have experienced declining research productivity during this period [5].

Nearly a third of survey respondents—primarily women in early or mid-career research positions—reported the amount of time they could dedicate to research was significantly reduced due to caregiving responsibilities, and anticipated that caregiving would impact their ability to conduct research for the next 12 months.

We heard from researchers struggling to balance personal and professional responsibilities while maintaining their productivity, in addition to concerns that ongoing grant funding and tenure review processes would further disadvantage them. These challenges were particularly compounded for postdoctoral fellows and early career researchers with caregiving responsibilities.

“As a woman and postdoc/resident, it has been SO hard managing both work and family life. I’m exhausted, and feel like I’m getting farther behind each day. Managing a career and family seems more and more impossible” – Postdoctoral fellow/Clinical Resident

“Women. Parents. Both are taxed with extraordinarily high caretaking responsibilities right now that make it impossible to maintain the usual 40+ hour work week. We’re drowning. We’re exhausted. We’re burnt out. And we are fully aware that there is a childless colleague who just submitted 3 papers in a month who is going up for the same award we are and feeling like he worked hard and deserves the accolades.” – Early career researcher

How we’re responding

Based on these findings and what we know about how other funders are responding,[4] we made changes to our programs and processes to better support BC health researchers who are most affected by the pandemic. This underpins our strategic commitment to develop and retain the health research talent BC needs, and foster a more equitable, diverse and inclusive health research system.

Current MSFHR award holders: We rolled out more flexible award policies for current MSFHR award holders, including extending reporting deadlines and expanding eligible expenses, and launched the MSFHR Research Continuity Fund to provide up to six months of additional salary support for eligible Research Trainees and Scholars whose awards end in 2020/21.

Peer review: Consistent with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research COVID-19 peer review policies, we introduced a new stipend to cover caregiving, phone, and internet expenses for MSFHR virtual peer reviewers. We are also developing additional guidance for our 2021 competitions to help MSFHR peer reviewers fairly and equitably assess applications in light of the pandemic.

2021 Scholar and Research Trainee competition: It’s clear that support for postdocs and early career researchers is important now more than ever, and we made changes to our 2021 Scholar and Research Trainee competitions to account for the impacts of COVID-19, including:

- Extending the eligibility window for both programs by one year to give postdocs and early career researchers more time to apply for, and potentially benefit from MSFHR support

- Providing the opportunity for applicants to complete an optional COVID-19 Impact Statement describing how the pandemic has affected their professional and personal lives

- Offering a three-year award term for all Research Trainee award recipients, unless a shorter term is requested, to provide greater funding stability to BC postdocs

- Requiring open-access publishing for any COVID-19-related research conducted by MSFHR award holders, in alignment with the Wellcome Trust’s statement on sharing research data and findings relevant to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak

Other 2021 programs: We are also taking what we’ve learned into consideration in the planning and design of our remaining 2021 funding programs, including the Health Professional-Investigator, Innovation to Commercialization and Convening & Collaborating/Reach awards, and we will have more details to share in January.

Closing thoughts

We’re hopeful that these changes will help support BC health researchers through the pandemic so they can do what they do best: develop the scientific evidence and discoveries we need to stay healthy.

We also know that coordinated efforts involving others in the health research system (e.g., universities, health authorities, other funders) are needed to help the research community recover. As a first step, we have shared the results of our information gathering process with key provincial and national stakeholders, and will explore opportunities to collaborate with them in developing a coordinated response.

Despite taking a comprehensive and multipronged approach to collecting information about the impacts of the pandemic in BC, we have some outstanding questions. We don’t know how representative our survey was of the BC health research workforce, or whether we captured the experiences of researchers facing additional challenges during the pandemic, including racialized groups and people living with disabilities.[5],[6]

We also know our data represent a specific point in time, and that we need to continue gathering information about the evolving impacts of the pandemic on the BC health research community. This will include filling gaps in our understanding about the experience of researchers facing systemic inequities and considering additional actions we can take as a funder to benefit BC health researchers who have been most affected.

We would love to learn from others who are exploring how COVID-19 is impacting health research activities, funding and careers. Leave a comment or get in touch (zsharman@healthresbcdev.wpengine.com) if you have questions, ideas or expertise to share.

Acknowledgements

With sincere thanks to the dedicated MSFHR team who made this project possible, including Julia Langton, Amanda Paleologou, Chong Chen, Zena Sharman, Chonnettia Jones, and Genevieve Creighton.

References

[1] See Nature’s (2020) Science After the Pandemic series

[2] Gibb, C., Nabavi, N., Karwi, Q., & Griffiths, E. (2020, May 4). Limiting the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Canadian postdoctoral scholars. Canadian Science Policy Centre.

[3] Gibson, E.M., et al. (2020). How support of early career researchers can reset science in the post-COVID world. Cell, 181(7), 1445-1449.

[4] Maas, B., et al. (2020). Academic leaders must support inclusive scientific communities during the pandemic. Nature Ecology and Evolution, 4, 997-998.

[5] Myers, K.R., et al. (2020). Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists. Nature Human Behavior, 4, 880-883.

[6] Stoye, E. (2020, April 17). How research funders are tackling coronavirus disruption. Nature.

[7] Woolston, C. (2020, July 31). ‘It’s like we’re going back 30 years’: how the coronavirus pandemic is gutting diversity in science. Nature.

[8] Witteman, H. Haverfield, J., & Tannenbaum, C. (2020). Positive outcomes of COVID-19 research-related policy changes. BioRxiv.