A 20-year journey of health research in BC: The beginning

31 March 2021

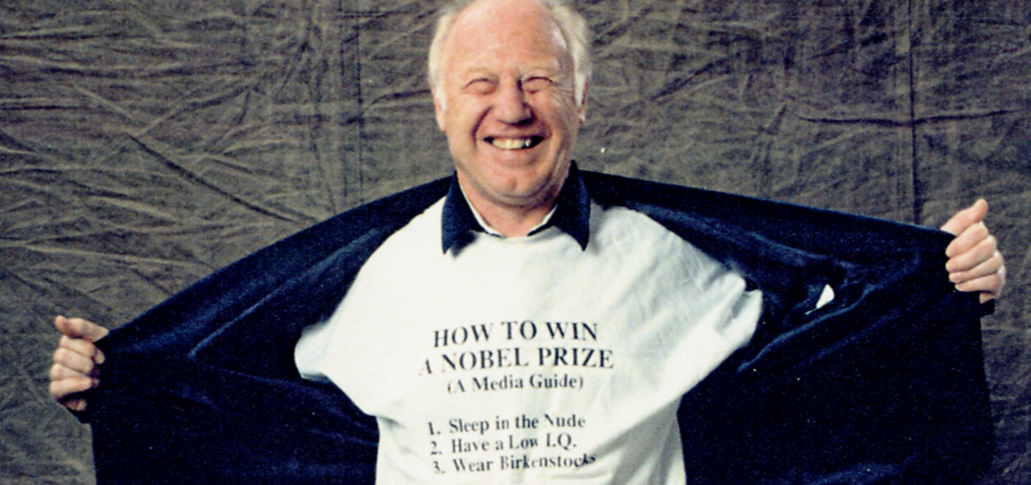

25th anniversary of Michael Smith’s Nobel Prize. Photo credit: Genome BC

Dr. Michael Smith: A life of paying it forward in health research

In 1956, 24-year-old Michael Smith, a budding scientist, moved from England to Vancouver to pursue his love of chemistry through a post-doctoral fellowship at the University of British Columbia.

He quickly fell in love with British Columbia’s rugged beauty, a passion he eventually shared with his three children, all of whom fondly recall family camping trips, sailing at Jericho and skiing at local ski hills.

At home, he was just ‘Dad’, the proper British chap who would mow the lawn on Sundays and whack their elbows off the table.

When he passed, the family was humbled by the number of organizations that asked to use his name to honour his memory.

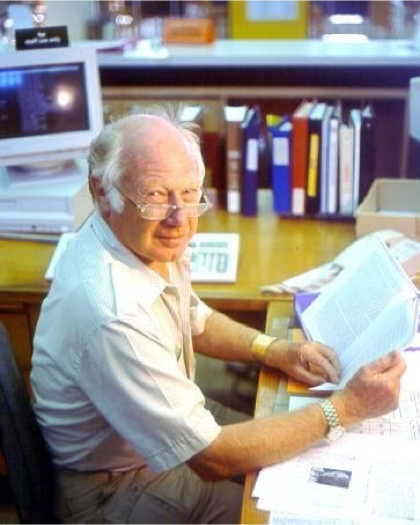

As a young researcher, Michael worried that academic research in BC was not well supported due to limited funding and more competitive hubs existing in other provinces. However, he persisted in the research sphere in BC, leading to an illustrious career in which he held senior positions at several organizations such as the Fisheries Research Board of Canada Laboratory in Vancouver and the Medical Research Council of Canada. But it was in the early stages of his career that Michael received funding from the British Columbia Health Research Foundation (the predecessor of the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research) and the National Cancer Institute of Canada, making it possible for him to stay in the province, conduct world-class research, and support other young researchers starting their careers. Michael remained appreciative of this funding, as it provided him a stable salary to conduct what he referred to as “follow-your-nose research.” It was also this funding that ultimately inspired a keen interest in supporting other young researchers.

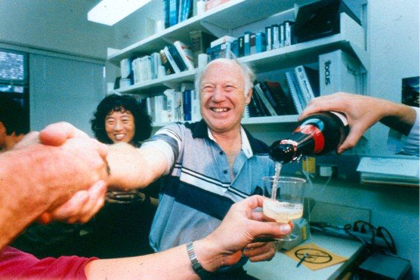

On October 13, 1993, Michael missed a very important 6 a.m. phone call that would not only change his life, but also the face of health research in BC. After then calling another Michael Smith who lived on the same street in Vancouver, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences called again and finally reached Michael to tell him that he had won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work in the development of site-directed mutagenesis. This award was shared with Dr. Kary Mullis for his invention of the polymerase chain reaction technique. For Michael, this prize was not his alone, but a collective achievement shared with his colleagues, including Caroline Astell, Shirley Gillam, Patricia Jahnke, Mark Zoller, and Clyde Hutchinson III. To honour their hard work and commemorate their contributions, he flew them, along with his loved ones, to Sweden for the awards ceremony.

From the moment he won the Nobel Prize, Michael knew he was going to donate the award prize back to researchers in BC. He thought carefully and critically about the missing players and voices and underfunded areas of research, then leveraged his success to improve the landscape of health research in the province he loved. He donated half of his prize money to researchers working on the genetics of schizophrenia, a notably underfunded area of research at the time. He donated the other half to Vancouver’s Science World and to the Society for Canadian Women in Science and Technology. Michael also successfully convinced the provincial and federal governments to match his prize money donations, creating a total endowment of more than $2 million.

Michael was a powerful advocate for health research who influenced national policy and helped to establish Canada’s Michael Smith Genome Sequencing Centre (GSC). The GSC has become an international leader in genomics, proteomics, and bioinformatics for precision medicine, which is creating novel strategies to prevent and diagnose cancers and other diseases, uncovering new therapeutic targets, and helping the world realize the social and economic benefits of genome science. The Centre is testament to the importance of funding and supporting health research, particularly in terms of the massive impact that early genomic research is having on today’s world.

Michael’s love for BC’s great outdoors persisted in everything he did. He was known for recruiting researchers by picking them up from the airport and taking them on a scenic drive along Spanish Banks to see the mountains and the ocean, followed by a dinner at a local restaurant — most often at Bishop’s Restaurant. Sadly, in 2000 Michael died far too early of cancer, a disease that is one of the focal points of the GSC. Fortunately, his legacy, values and the impact he made on health-care research in BC live on.

Today, the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research is synonymous with the values Michael held, lived and shared in his life — in particular, continuing to invest in talented researchers in British Columbia. We believe he would be proud of the organization that honours his name, and the researchers who choose to conduct health research in our beautiful province.

Before Michael Smith and his colleagues, the methods for producing gene mutations, similar to the natural evolution process, were crude, slow, and produced mutations at random. This meant having extremely rigorous selective procedures to locate the mutations of interest. The tool Michael and his colleagues invented — site-directed mutagenesis — revolutionized the face of molecular biology.

Site-specific mutagenesis allowed researchers to introduce mutations at precise positions along the DNA, helping us better understand how genes work, and what happens when they go wrong. This level of precision has sped up the process of gene mutations exponentially, allowing scientists researching health challenges such as cancer and HIV/AIDS to move faster towards finding potential cures.

Learn more:

Michael Smith: Organic Chemistry — Science.ca

Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1993: Dr. Michael Smith — Nobel Prize